So you (or rather I) have this legacy code that must be maintained. It has all the classic symptoms:

- it looks like it was written before const, smart pointers or RAII were a thing

- the author was a big fan of (overly) defensive programming

- either not much thought went into the overall design or over time the design was compromised by the extensions that were made later

- there is a lack of (proper) tests

Tests

refactoring without tests is just changing sh*t. – Hamlet D’Arcy

Before you start changing anything I would suggest you get proper tests in place if they are not already there. A comment I got at a presentation was: “yes, but to add tests I need to decouple stuff, add interfaces, and that is also a change, so I can’t add any tests”. Well, true, you have to start somewhere, a good set of integration tests can be a good start, test what you can, add interfaces as you go. There is always some risk of mistake, but as adding interfaces should not change any behavior, it is often a can-be-judged-good-by-inspection kind of change. Making other changes such as ‘fixing this minor thing at the same time’ should be carefully avoided.

About defensive programming

Don’t get me wrong, Defensive programming in itself can be a useful thing or even vital in some cases. The gist of defensive programming is “do not trust other software developers to do the right thing” with your code. However, in many cases ‘we’ ourselves are the ‘other software developers’ and if you can not even trust yourself to use you own code right and you do checks everywhere, then this will come at a great costs in terms of run-time and readability/maintainability. So it stands to reason that we need to strike a balance here. Also, even if we do want to do checks against incorrect usage, there are tools that can help reduce the time and lines of code spend on doing it.

Let see some examples, so we know what we’re dealing with:

// example1: check, check, double check.

#include <assert.h>

#include <iostream>

class Bar

{

public:

void barMethod() { std::cout << "boo\n"; }

};

void foo2(Bar* bar)

{

assert(bar != nullptr);

bar->BarMethod();

}

void foo1(Bar* bar)

{

if (bar == nullptr) return;

foo2(bar);

}

void foo()

{

Bar b;

foo1(&b);

}

Lets look at motivation first, what goes on in this code? The author of foo1() was concerned that someone could pass nullptr and decided to check for this condition and do nothing in that case. While this prevents a crash, if passing nullptr is truly a programming error, this will effectively cloak a bug and make it hard to detect.

The author of foo2() takes a different approach and decides that passing nullptr is a precondition violation of the method and an assertion is in order. In this case an assertion will trigger in debug builds but in production nothing will prevent it from crashing. This sounds even worse, right?

In fact both methods had a pre-condition that bar can never be null but by the way it is called, we can be absolutely sure that bar is never null. However, if some future author changes things around, that might no longer be the case. So if for some reason bar does becomes null (or any other invalid value for that matter) I would want to know about it as soon as possible. Also I would like the code to express that this was indeed the intended precondition.

There are several ways to achieve this, first of all lets look at references:

#include <assert.h>

#include <iostream>

class Bar

{

public:

void barMethod() { std::cout << "boo\n"; }

};

void foo2(Bar& bar)

{

bar.barMethod();

}

void foo1(Bar& bar)

{

foo2(bar);

}

void foo()

{

Bar bar;

foo1(bar);

}

Here references were used to express that bar should always have a valid value. The methods foo1() and foo2() do not explicitly check this, however, if bar does become invalid, the code will likely crash. I like this style personally and use it whenever possible, I actually prefer to crash to ignoring the call or getting an assertion since this will expose the bug early, very likely in a unit test.

Looking back at the first example: If the call is ignored, the bug will be silent and likely rear its ugly head in future unpredictable ways. Both methods will only catch the case when the value is exactly null and will not catch the case where the value is for example -1, ‘0xdddddddd’, or something else.

It is useful to remember this, because it can introduce differences in behaviour between debug and release builds. Depending on your environment, in debug builds, variables can be zero’d out and memory filled with 0xcccccccc, 0xfeeefeee or 0xdddddddd depending on if it is just allocated, initialised or freed.

The assertion can in some cases hang a continuous integration system because it pops up a message dialog by default, however, as far as I know this applies to MSVC only.

You might argue, is a crash not always worse then no crash at all? I think it is not; a program continuing to run with unknown behaviour is in my opinion much worse than a crash because it is a potential later crash that will be unpredictable and much harder to debug then the initial problem. If we’re going to crash we should do it sooner so we can catch it before it reaches production.

There are also cases where references are not an option, for example in data structures where the pointer can never be null but it should be re-assignable to point to a different object. For those cases the not_null<> template from the GSL seems to work well.

#include <iostream>

#include <gsl/pointers>

class Bar

{

public:

void barMethod() { std::cout << "boo\n"; }

};

void foo2(gsl::not_null<Bar*> bar)

{

bar->barMethod();

}

void foo1(gsl::not_null<Bar*> bar)

{

foo2(bar);

}

void foo()

{

Bar bar;

foo1(&bar);

}

Now this is still pretty good; each method explicitly states its the caller’s responsibility to know that the pointer is valid. And if it is not, this will fail fast by crashing. Both ways achieve to at least document the precondition and allow removal of the duplicated null checks at every level.

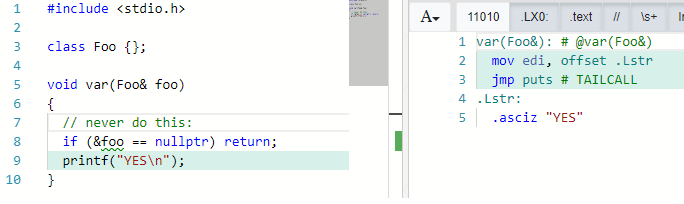

There are a couple of problems that can arise when applying this change. When changing the method prototype to use references there will be a point where the existing pointer has to be dereferenced to assign to the reference. You have to be sure the pointer is not null before turning it into a reference, because dereferencing a nullptr is UB. In practice it will probably not crash until the reference is actually used, but this can be tricky: (warning, bad code ahead)

Here you can see that checking a reference for null can have interesting side effects. The check is completely optimized out, fortunately clang is nice enough to emit a warning when this happens.

At first glance you might expect this to be a compiler bug, however, it is not. The reasoning goes something like this:

- you cannot assign a reference with a null value (int& i = nullptr will not compile)

- dereferencing a pointer containing the value nullptr causes undefined behavior (int &i = *ip; is UB when ip is nullptr)

- so: a reference can never have the value nullptr

- this means the if-statement can never be true and so the whole if-statement can be optimized out.

Long story short: (1) make sure the pointer you dereference is not nullptr before passing it to a method taking a reference and (2) don’t do any checking on references, it does not make any sense and will have unexpected results.

1: void foo2(Bar* bar)

2: {

3: assert(bar != nullptr);

4: bar->BarMethod();

5: }

A side-story on the ASSERT case above, it can have interesting side effects on static code analyzers! The analysis goes like this:

- line 3, analyzer reads: you’re telling me bar could be nullptr, i’ll make a note of that (why would you otherwise check for that)

- line 4, analyzer reads: you’re calling a method on ‘bar’, let me check if that could be nullptr, err, YES, it could be! I better warn the user to do a null-check!

Actually removing the assert gets rid of this false-positive warning from the static analyzer.

Summary for this chapter about defensive programming style:

- some code may rely on the fact the method did nothing when called with a nullptr, so removing the null check and changing to a reference in that case will introduce a crash at best and UB otherwise.

- some code may need to re-assign the pointer so using references are not always an option

- for places where reference can be used a crash will occur only when the reference is actually used

- not_null can be used in both places and can be configured to crash when it is assigned a null value, which is when I want to know about it.

Conclusion: using references in places where pointers are passed that may never be null is an improvement over raw pointers, since it is documenting the precondition. But not_null<> is more explicit in expressing this intent and has the added benefit of earlier error detection.

Dealing with raw pointers that manage lifetime

So in C++ we have smartpointers right? Raw-pointers? so passé! NO. Let me be clear: raw pointers are great, always have been, likely always will be. However, owning raw pointers, those are or should be a thing of the past. An owning raw pointer looks like this:

Foo * foo = new Foo();

Do you see the special syntax used to indicate and make very clear that this raw pointer is an owning raw pointer, meaning that the method that gets this pointer is responsible for cleaning up the allocated memory? You do not see it? Makes sense, that is because there is nothing that separates this pointer from any other kind of raw pointer.

void f()

{

Foo * foo = new Foo();

g(foo);

h(foo);

}

void g(Foo* foo) {} // non-owning raw pointer

void h(Foo* foo) { delete foo; } // owning raw pointer

A general advice often heard is:

do not create owning raw pointers

However, what to do when you (again: I) have a 15 year old code base where this happens all over the place?

class Message{};

Message* receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return new Message();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(Message* p) { p1(p); }

void p1(Message* p) { p2(p); }

void p2(Message* p) { p3(p); }

void p3(Message* p) { delete p; }

};

Here, because it is a toy example, it is easy to see the Message is allocated in the receiveMessageFromHardware() method and it is deallocated in p3(). However in practice, this can be a long and interesting journey through the code to find all the places that allocate Message objects and all end-paths that (should) deallocate the Message object. Also, if the full path to p3() is not followed, due to an error condition, who will deallocate?

The first thing to do is probably just to annotate the code to make clear the raw pointers are actually owning in this case:

#include <gsl/pointers>

class Message{};

template <typename T>

using owner = gsl::owner<T>;

gsl::owner<Message*> receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return new Message();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(owner<Message*> p) { p1(p); }

void p1(owner<Message*> p) { p2(p); }

void p2(owner<Message*> p) { p3(p); }

void p3(owner<Message*> p) { delete p; }

};

This is a great improvement to do as a first step, it documents/makes explicit the fact that the raw pointers are owning raw pointers. The gsl::owner<> template is very simple:

template <class T, class = std::enable_if_t<std::is_pointer<T>::value>>

using owner = T;

That’s all she wrote… its basically a template doing exactly nothing except check that the argument passed is a pointer type. This in itself is a very useful step in the process of documenting ownership and by doing so making the code more readable. The assumption that the pointer owns the object and thus the object will either live until the end of the method or it will be passed onto another method is now explicitly encoded in the type of parameter. Note that static analyzers can know about gsl::owner<> and can now help you to find the cases where an owning raw pointer was passed but not deallocated.

The next most obvious modern c++ solution/step is in many cases introducing a std::unique_ptr<Message> and moving the ownership through the chain, like so:

#include <memory>

class Message{};

std::unique_ptr<Message> receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return std::make_unique<Message>();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) { p1(std::move(p)); }

void p1(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) { p2(std::move(p)); }

void p2(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) { p3(std::move(p)); }

void p3(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) { }

};

int main()

{

Engine().process(receiveMessageFromHardware());

}

Now the code has improved in multiple ways:

- it is clear about the ownership of the Message object

- the correctness in terms of deallocation of the Message object no longer depends on the error path, early return or exceptions being thrown

When written like this it does not matter if a function exits early by returning mid-processing or whether an exception occurs, the Message object will always be correctly cleaned up and you do not have to write any cleanup code to make that happen.

However, introducing std::unique_ptr<> throughout the code can be a challenge, the Message object may be passed through a lot of layers, through a queue, passed over multiple threads etc. What if you cannot or just don’t want to change everything in a single changeset?

#include <memory>

class Message{};

Message* receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return new Message();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(Message* p)

{

p1(p);

}

void p1(Message* p) { p2(p); }

void p2(Message* p) { p3(std::unique_ptr<Message>(p)); } // note change

void p3(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) {} // note change

};

int main()

{

Engine().process(receiveMessageFromHardware());

}

In this example, we only changed the method that does the delete and its caller, but nothing else. This can be very nice, because now we can start refactoring bottom-up but we don’t have to change everything in one go. To make the example more interesting, below, I have added two possible ‘tail calls’. It does not matter whether the Message is passed into p3() or p4(), both will take ownership and properly deallocate at the end of their execution.

#include <memory>

extern bool IsConditionMet();

class Message{};

Message* receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return new Message();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(Message* p)

{

p1(p);

}

void p1(Message* p) { p2(p); }

void p2(Message* p)

{

if (IsConditionMet())

{

p3(std::unique_ptr<Message>(p));

}

else

{

p4(std::unique_ptr<Message>(p));

}

}

void p3(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) {}

void p4(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) {}

};

int main()

{

Engine().process(receiveMessageFromHardware());

}

The approach does not just work bottom-up, here is a top-down example:

#include <memory>

class Message{};

std::unique_ptr<Message> receiveMessageFromHardware()

{

return std::make_unique<Message>();

}

class Engine

{

public:

void process(std::unique_ptr<Message> p) { p1(p.release()); } //notice release()

void p1(Message* p) { p2(p); }

void p2(Message* p) { p3(p); }

void p3(Message* p) { delete p; }

};

int main()

{

Engine().process(receiveMessageFromHardware());

}

Here we used make_unique<> to allocate the object and in process() took the ownership from the unique_ptr and continue passing the ‘old way’ to p2(). Theoretically, just could even start on both sides at the same time and work towards the middle, but I’m not sure that would serve any purpose.

const correctness

Another thing that is useful to document is the intention a method is not supposed to change anything. In my code base this was not really done (anywhere). The problem with adding const retrospectively is that making a method const will probably mean you have to make its callers const as well and this can snowball really quick. A good way I found to start adding it is to use a static analysis tool (I used Resharper C++) to tell you what methods can be made const (leaf methods) that are not const right now. However I should mention at this pointer that adding const in an inheritance hierarchy (any virtual method) can break existing code. This is because as const is part of the function prototype, for example:

class Base

{

virtual void bar() = 0;

};

class Foo : public Base

{

virtual void bar() const = 0; // by adding const here, still compiles but Foo::bar no longer overrides Base::bar!

};

class Foo2 : public Base

{

virtual void bar() const override = 0; // compiler error! bar did not override any base class methods

};

So to deal with this, when adding const to a virtual method the overrides anything, always made sure to also add the override keyword.

After you have done this, re-running the tool will get you the next level of methods to make const, if you repeat this cycle a few (5-10) times you can quickly improve the const-correctness of a project a lot. The reason why this approach is nice is because you can stop at any time and the effects do not snowball because you started by changing the leaf methods and are working your way up the call chains.

smartpointers and RAII types

Custom destructor on unique_ptr can be used to wrap resources

// ignore (windows plaform stuff)

using HANDLE = void*;

#define INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE ((HANDLE)(-1))

#define PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION (1)

#define FALSE (false)

extern void CloseHandle(HANDLE);

extern HANDLE OpenProcess(int dwDesiredAccess, bool bInheritHandle, int dwProcessId);

extern int GetCurrentProcessId();

// ignore (windows plaform stuff)

#include <memory>

struct HandleDeleter

{

using pointer = HANDLE;

void operator()(pointer p) const;

};

typedef std::unique_ptr<void, HandleDeleter> Handle;

void HandleDeleter::operator()(pointer p) const

{

if (p != nullptr && p != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

CloseHandle(p);

}

int main()

{

// now we can write:

Handle handle(::OpenProcess(PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION, FALSE, GetCurrentProcessId()));

// instead of:

HANDLE h = ::OpenProcess(PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION, FALSE, GetCurrentProcessId());

CloseHandle(h); // may be needed in multiple branches

}

more smaller things

I found these ‘tricks’ handy:

- create a quick/convenient way to add logging in

anyplace - rewrite typedef as aliases using the using syntax

Example code for a windows specific way to make adding logging in any class a one-liner:

cdbg << "some value: " << 4 << ", and another: " << 2 << "\n";

The cdbg object is a std::basic_ostream<> that writes anything it gets passed to the OutputDebugString API. By using this approach a tool like DebugView++ can be used to monitor and filter these message. If you happen to be on another platform you can just swap out OutputDebugString for std::cout or your own favorite log function. The point here is: adding an easy to use facility to quickly add some logging get really help you understand code more quickly.

GitHub link to basic_dbgstream

Example of rewriting typedef’s to make them more readable:

// write:

using HANDLE = void*;

// instead of:

typedef void* HANDLE;

// and write:

#include <type_traits>

using FunctionPtr = std::add_pointer<void()>; // declare a pointer to a `void()` function

// instead of:

typedef void (*FunctionPointer)(); // oldschool pointer to a `void()` function

using the dropbox NN<> template

I have not written this part yet, check back for more later….check this video to wet your appetite Youtube video on NN<> Github repo for NN<>

what about smart pointers (shared_ptr and unique_ptr) and gsl::not_null

Earlier versions of the GSL did not allow you to wrap std::unique_ptr<> or std::shared_ptr<> in a not_null<> template, however, this seems to work ok now:

class Message {};

gsl::not_null<std::shared_ptr<Message>> msg = std::make_shared<Message>();

I need to try and play with this some more and will update this post after I do.

what about a boost::shared_ptr<> “infected” code base?

When smartpointers were ‘new’ and not in the standard library yet (C++/03 era), boost had an implementation already. Many early adopters realized using a smartpointer was superior to using raw pointers for ownership. However, in these early days there was no such thing as move-semantics yet. As a consequence many developers adopted boost::shared_ptr<> as it could be copied easily and life was good (or so it seemed).

The major drawback of use boost::shared_ptr<> or any shared pointer, is that there is no explicit transfer of ownership. How long an object will live will depend on the last user and while this sounds reasonable, it encourages sloppy lifetime management and very often these program suffer from shutdown problems (crashes).

I have not had to refactor such a project yet, but I expect to take a similar approach for these project as I do for projects using raw owning pointers, start by nailing down the lifetime of objects. Replace boost::shared_ptr<> parameters with references or not_null<> pointers for methods that do not participate in the lifetime management of the object.

Final words

This post is a work in progress, I will update it after I have more experience applying these techniques or discover new ones. std::string_view is up next… stay tuned….

References: Twitter feed

Tweet